Background

Events from the Year 1938

This list of dates briefly illuminates singular episodes that lead to the Anschluss and Kristallnacht pogrom in Austria in 1938. Additional material about individual topics can be found under “Sources,” “External Links and Literature,” and “Resources.”

Photo in the background: Adolf Hitler gives a speech on March 15, 1938 at Vienna’s Heldenplatz square

(Photo: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1987-0922-500 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Content

- February 12, 1938: The Berchtesgaden Agreement

- February 15–16, 1938: Government shake-up and Schussnig’s fifth cabinet

- February 24, 1938: Kurt Schuschnigg’s speech in the Vienna Parliament

- March 9, 1938: Schuschnigg announces the Anschluss Referendum

- March 10, 1938: Hitler gives the order to prepare the invasion of Austria

- March 11, 1938: Schuschnigg’s resignation

- March 11, 1938: The Pledge of Seyss-Inquart as Federal Chancellor

- March 12, 1938: German troops invade Austria

- March 13, 1938: The Anschluss Law

- March 15, 1938: Hitler’s speech on Heldenplatz square in Vienna

- After the Anschluss: Terror against Jews and political opponents continues to increase

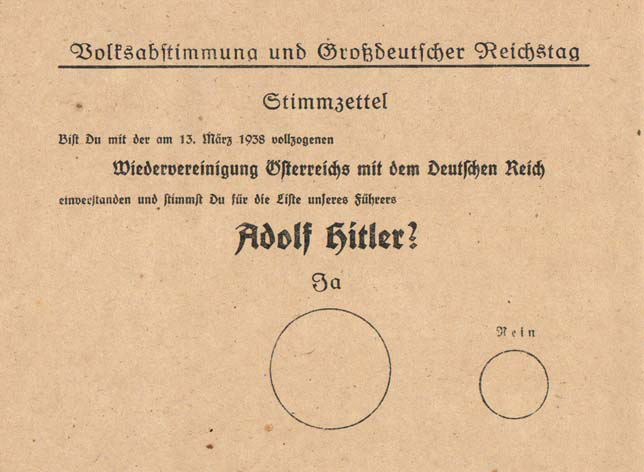

- April 10, 1938: Referendum

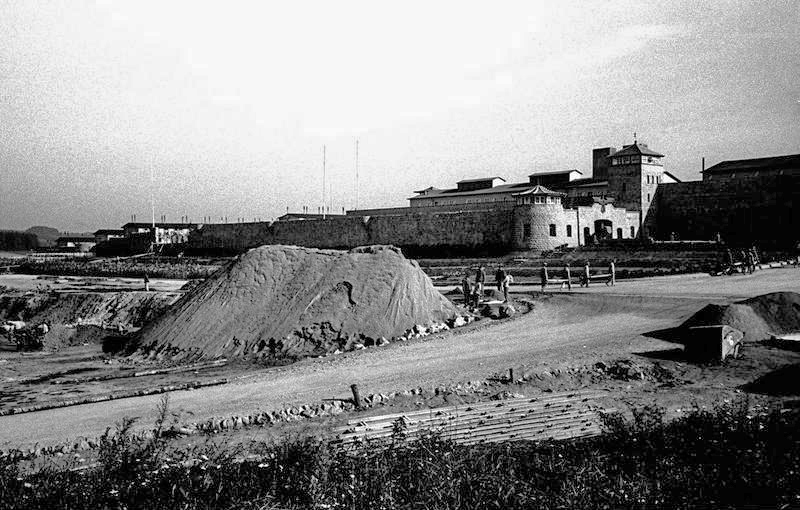

- August 8, 1938: Establishment of the Mauthausen Concentration Campn

- After the Anschluss: Jewish Immigration to Palestine

- November 7, 1938: Attack on Legation Secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath

- November 9, 1938: Kristallnacht Pogrom

- After the Kristallnacht Pogrom: Start of Kindertransports

With these links you can jump directly to the individual chapters.

February 12, 1938

The Berchtesgaden Agreement

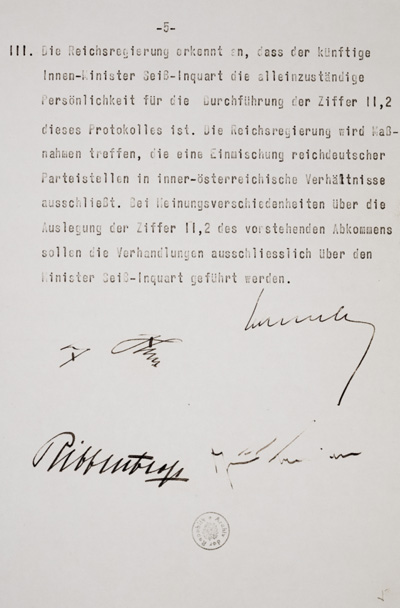

On February 12, 1938, Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg met with Adolf Hitler in the Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden to negotiate the German-Austrian question. These negotiations did not, however, take place on equal footing, as Hitler continuously threatened Schuschnigg with an immediate invasion of German troops.

Due to a series of terrorist attacks, the Nazi Party (NSDAP) was banned in Austria in 1933. In addition to reversing the ban on the Nazi Party, Hitler demanded that Austria also appoint Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Minister of the Interior and Security and grant amnesty for imprisoned Nazis. Schuschnigg was nonetheless still able to prevent the Nazis from occupying the departments of the army and ministry of finance. After signing, Schuschnigg was granted three days to implement the contents of the agreement

Bauer, Kurt (2017): Die dunklen Jahre: Politik und Alltag im nationalsozialistischen Österreich 1938 bis 1945. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer.

Bauer, Kurt (2001): Sozialgeschichtliche Aspekte des nationalsozialistischen Juliputsches 1934. Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie aus der Studienrichtung Geschichte. Wien. Verfügbar unter: kurt-bauer-geschichte.at

Schuschnigg, Kurt (1946): Ein Requiem in Rot-Weiß-Rot. Zürich: Amstutz & Herdeg. Gekürzter Auszug auf: derstandart.at

Urbanek, Gerhard (2011): Realitätsverweigerung oder Panikreaktion? „Vaterländische“ Kommunikationspolitik in Österreich zwischen Juliabkommen 1936, Berchtesgadener Protokoll und „Anschluss“ 1938. Wien: Universität Wien. Verfügbar: unterothes.univie.ac.at (PDF)

The last page of the Berchtesgaden Agreement with the signatures of Adolf Hitler and Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Foreign Minister of the German Reich, as well as the signatures of Austrian Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg and Foreign Minister Guido Schmidt (Photo: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv).

Paul Rona reports:

It was during the time when Schuschnigg met with Hitler in Berchtesgaden. When he came back, there was a large family gathering in Café Ritter. That was the first time I was allowed to be present for such a serious discussion. Emmerich Strasser said that he’d made an inquiry: if Hitler is to invade Austria, then the youth should get out as quickly as possible. The other family members will be able to withstand Hitler. The family is going to stay together – they’d helped each other out up until then – and now they’ll help each other a little bit more. They’ll stick it out for the couple of years that it might take. I remember he spoke of years.

Original recording of Paul Rona (Source: Centropa)

Februar 15–16, 1938

Government shake-up and Schussnig’s fifth cabinet

The orders from the Berchtesgaden Agreement were implemented on February 15, 1938 by the newly-appointed government. Kurt Schuschnigg remained as the head of the government. The most significant change in the cabinet was Arthur Seyss-Inquart’s appointment as Minster of the Interior and Security, which allowed him to assume command of the police force.

Hitler’s demand for “amnesty for all persons punished judicially or by police for National Socialist activities” was put into force, though it was not only individuals with Nazi attitudes and misdemeanors who profited from the amnesty – it also included Communists and revolutionary Socialists, so that the amnesty was “open to the left and right.”

(Photo: Wikimedia/Public Domain)

Bauer, Kurt (2017): Die dunklen Jahre: Politik und Alltag im nationalsozialistischen Österreich 1938 bis 1945. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer.

Reiter-Zatloukal, Ilse (2012): Die Begnadigungspolitik der Regierung Schuschnigg. Von der Weihnachtsamnestie 1934 bis zur Februaramnestie 1938. In: BRGÖ 2012/2, S. 336-364.

February 24, 1938

Kurt Schuschnigg’s speech in the Vienna Parliament

On February 24, 1938, Chancellor Kurt Schuschnigg delivered a speech before the Federal Assembly that caused a sensation even beyond the Austrian borders. The speech is often interpreted as the answer to the one given by Hitler on February 20, 1938, in which he spoke of the problem of “constitutional separation of the Reich.” Schuschnigg emphasized that the Berchtesgaden Agreement was to be complied with.

In his speech, Schuschnigg also highlighted the absoluteness of Austrian sovereignty: “We know exactly that we can reach and have reached that limit, behind which it is quite clear: Up until here and no further! (…) And because we are resolute, victory is beyond doubt. Therefore, comrades: until death! Red – White –Red! Austria!”

Hitler, Adolf (1938): Reichstagsrede vom 20.02.1938.

Schuschnigg, Kurt (1938): Rede vor der Generalversammlung am 24.02.1938.

Scheidl, Hans Werner (2013): Auf: Kurt Schuschnigg warnt die österreichischen Nationalsozialisten (diepresse.com)

Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung Deutschland: Vor 80 Jahren: Einmarsch der Wehrmacht in Österreich – Wie heute dort an den “Anschluss” erinnert wird

Haus der Geschichte Österreich: Zeituhr 1938

Rede von Kurt Schuschnigg am 24. Februar 1938 vor der Bundesversammlung im Originalton auf der Website der Österreichischen Mediathek

March 9, 1938

Schuschnigg announces the Anschluss Referendum

During a speech in Innsbruck on March 9, 1938, Chancellor Schuschnigg announced a referendum on the Austrian annexation to the German Reich, although this was officially presented as a public opinion poll. The poll was set for Sunday, March 13, 1938 in order to impede the Nazi’s election canvassing, since they were, per the Berchtesgaden Agreement, permitted to operate legally again and were pushing themselves more drastically into public view. Schuschnigg chose the text to be used in the poll. This he chose deliberately to ensure that as many voters as possible would join him:

“For a free and German, independent and social, for a Christian and united Austria! For peace and work and the equality of all those who pledge themselves to the people and the Fatherland.”

Haidinger, Martin/Steinbach, Günther (2009): Unser Hitler. Die Österreicher und ihr Landsmann. Salzburg: Ecowin Verlag.

Urbanek, Gerhard (2011): Realitätsverweigerung oder Panikreaktion? „Vaterländische“ Kommunikationspolitik in Österreich zwischen Juliabkommen 1936, Berchtesgadener Protokoll und „Anschluss“ 1938. Wien: Universität Wien. Verfügbar unter: othes.univie.ac.at (PDF)

In a film by the Vienna police from the ORF archive you can see how people are soliciting the “referendum” on the streets – to be viewed at science.orf.at

March 10, 1938

Hitler gives the order to prepare the invasion of Austria

Among the reasons for Hitler’s order to invade, two points were deciding factors for him. Perhaps the most important was that Hitler feared a poor poll result. The other was his annoyance by Schuschnigg’s autonomous advance. The order to prepare the invasion was directed to Ludwig Beck, the head of the general staff and 8th Army.

During this time, demonstrations were taking place in Austria led by those loyal to the government and by left-wing Austrians who spoke out for governmental autonomy.

(Foto: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv)

Haidinger, Martin/Steinbach, Günther (2009): Unser Hitler. Die Österreicher und ihr Landsmann. Salzburg: Ecowin Verlag.

Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstands: 1938, unter: http://ausstellung.de.doew.at/m9sm104.html [zuletzt abgerufen am:24.08.2018].

March 11, 1938

Schuschnigg’s resignation

On March 11, 1938, Hitler decreed that armed forces were to march into Austria in order to “produce constitutional conditions and halt acts of violence against the German-minded population.” An ultimatum was issued prior to this, stating that the referendum was to be delayed 14 days. Germany further increased its pressure on the Austrian government as a result. In the early evening, Schuschnigg announced his resignation on Austrian radio and informed the Austrians of the German ultimatum “to appoint a chancellor and a government in accordance with the recommendations of the German Reich government.”

He ended his address with the words: “I take my leave at this hour with a German word and heartfelt wish: God save Austria!”

Kurt Schuschnigg’s final radio address as Austrian Chancellor on March 11, 1938

Source: Wikimedia/Public Domain

Kurt Rosenkranz reports:

We were at my grandparent’s place, it was Shabbat. All of a sudden we heard on the radio, “God save Austria!” Those were Schuschnigg’s last words, and my mother wept bitterly because she knew what was coming.

It had no effect on me. But on Saturday morning, the looting began in Vienna.

Original recording of Kurt Rosenkranz (Source: Centropa)

Robert Walter Rosner reports:

On Friday March 11, 1938, there were rallies in the afternoon, and I was in the city and watched. When I got home I found out that Schuschnigg had abdicated and my father said from the first moment: we have to go!

Urbanek, Gerhard (2011): Realitätsverweigerung oder Panikreaktion? „Vaterländische“ Kommunikationspolitik in Österreich zwischen Juliabkommen 1936, Berchtesgadener Protokoll und „Anschluss“ 1938. Wien: Universität Wien. Verfügbar unter: othes.univie.ac.at (PDF)

Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung Deutschland: Vor 80 Jahren: Einmarsch der Wehrmacht in Österreich – Wie heute dort an den “Anschluss” erinnert wird

Haus der Geschichte Österreich: Zeituhr 1938

March 11, 1938

Seyss-Inquart sworn in as Austrian Chancellor

Directly following Schuschnigg’s resignation, Reichsmarschall Göring demanded that Seyss-Inquart take over the Austrian government. Wilhelm Miklas, the Austrian President, opposed the plans, thus prompting Göring to instruct Seyss-Inquart to send a telegram to Berlin expressing the Austrian government’s request for Germany’s assistance in “restoring peace and order and preventing bloodshed.”

Although the telegram was never sent, State Secretary Wilhelm Keppler forwarded the confirmation and Hitler issued the order to invade. Under this pressure, Seyss-Inquart was sworn in as Austrian Chancellor shortly before midnight.

Urbanek, Gerhard (2011): Realitätsverweigerung oder Panikreaktion? „Vaterländische“ Kommunikationspolitik in Österreich zwischen Juliabkommen 1936, Berchtesgadener Protokoll und „Anschluss“ 1938. Wien: Universität Wien. Verfügbar unter: othes.univie.ac.at (PDF)

March 12,1938

German troops invade Austria

In the early hours of March 12, around 65,000 soldiers and police officers marched into Austria. They did not encounter resistance – often they were received with much rejoicing from the Austrian population. Prior to this, Schuschnigg had ordered the Austrian military not to resist the German troops.

In the afternoon, Adolf Hitler crossed the border near Braunau am Inn, his birthplace, and later delivered a speech in Linz in which he announced the Anschluss. Heinrich Himmler took over the police force in Vienna and Chancellor Seyss-Inquart set off for Linz to plan with Hitler the immediate annexation to the German Reich. The Austrian population’s great approval of the invasion moved them to abandon their original plan of initially preserving a kind of partial sovereignty and to immediately implement the Anschluss.

Lucia Heilman reports:

On March 12 German troops marched into Austria. I was eight years old and went by myself to Heldenplatz square, since there was an event there. As I reached the vicinity of Heldenplatz square I couldn’t go any further – there were so many people on the Ring Road. I stood there and heard the yells, the roaring, and this cry, “Heil, Heil, Heil…” and I knew that I didn’t belong there. I found these cries and this atmosphere very threatening. I stood there for a while, listened, and saw people climbing trees so they could get a better look. And the cries didn’t stop. I came home completely distraught.

(Photo: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 137-049271 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Paul Back reports:

On March 12 1938 I saw airplanes black out the sky, a whole host of airplanes, real squadrons.

First off, the Nazis wanted to demonstrate their power and, secondly, they actually had things to transport in order make themselves at home here. You began seeing people in uniform and boys in Hitler Youth shirts walking around. They were Austrians – the Germans weren’t in Vienna yet. They didn’t come directly to Vienna, since they were initially delayed by people cheering them on along the way. The Wehrmacht curried favor with the Viennese by offering food – with a field kitchen on Heldenplatz.

Original recording of Paul Back (Source: Centropa)

Haidinger, Martin/Steinbach, Günther (2009): Unser Hitler. Die Österreicher und ihr Landsmann. Salzburg: Ecowin Verlag.

Urbanek, Gerhard (2011): Realitätsverweigerung oder Panikreaktion? „Vaterländische“ Kommunikationspolitik in Österreich zwischen Juliabkommen 1936, Berchtesgadener Protokoll und „Anschluss“ 1938. Wien: Universität Wien. Verfügbar unter: othes.univie.ac.at (PDF)

March 13, 1938

The Anschluss Law

On March 13, the cabinet of Seyss-Inquart’s government passed the “Law on the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich,” so that Austria would henceforth be a country of the German Reich (Article 2). In Article 3 of the law, a “free and confidential referendum of German men and women over 20 years of age on reunification with the German Reich” was announced, scheduled to take place on April 10, 1938. It must be mentioned, however, that this had nothing to do with a free and confidential election. President Miklas refused his signature and resigned.

March 15, 1938

Hitler’s speech on Heldenplatz square in Vienna

On March 15, 1938, Hitler delivered a speech before a large crowd of people (most estimations account for 250,000 in attendance) on Heldenplatz square in Vienna, during which he declared the “entry of his homeland into the German Reich.” Visual and audio documentation indicate that the crowd present enthusiastically attended the rally.

Before Hitler delivered his speech, Seyss-Inquart spoke to the crowds and proclaimed the “hand-over” to Hitler: “As the last supreme institution of the Federal State of Austria, I announce to the Führer and Reich Chancellor the implementation of the lawful decree as per the will of the German people and their leader: Austria is a country of the German Reich.”

(Photo: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-1987-0922-500 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Dokumentationsarchiv des Österreichischen Widerstands: Der 15. März, Wiener Heldenplatz.

Available here: https://www.doew.at/cms/download/78t22/maerz38_heldenplatz.pdf [PDF, last accessed on: September 12, 2018].

Transcriptions of the speeches on the website of the Documentation Center of Austrian Resistance: https://www.doew.at/cms/download/78t22/maerz38_heldenplatz.pdf (PDF, S. 4-5)

Original recording of Hitler’s speech at the Austrian Media Library

After the Anschluss:

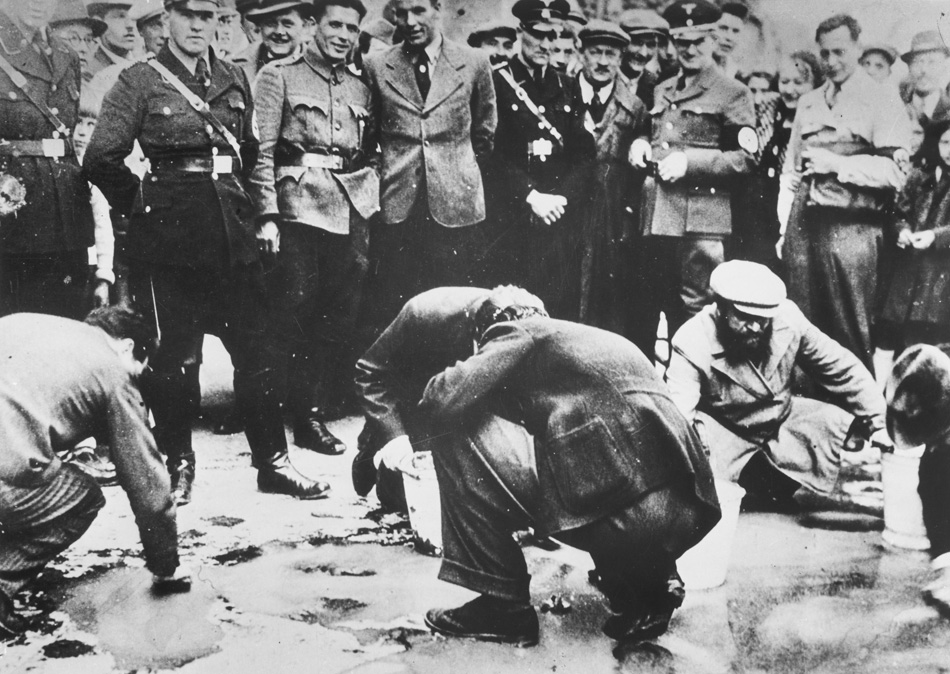

Terror against Jews and political opponents continues to increase

Directly following the Anschluss, the terror against Jewish people and “opponents of the regime” began. The image of the so-called “Reibpartien” – a term describing the Jews of Vienna who were forced to remove political slogans that had come about prior to Schuschnigg’s announced referendum – became the symbol of this early terror. The term “Reibpartie” is considered downplayed. Victims were publically humiliated, which showed that a large portion of the population maintained a dehumanizing attitude towards Jews.

In addition to humiliations in public space, numerous people were imprisoned shortly after the Anschluss. It is estimated that around 70,000 political opponents and Jews had already been imprisoned just days after the Anschluss. Furthermore, numerous businesses with Jewish owners were looted and “Aryanized,” which initially took place “wildly,” meaning not organized. Starting in June 1938, these “wild actions” deviated from the controlled and systematically organized campaigns.

Lucia Heilman reports:

A short time later [after the Anschluss], the director of the school came into the classroom and said that the Jewish children had to leave the class. We took our schoolbags, put away our pencil cases and notebooks, and left the classroom. That felt like a terrible humiliation: exclusion from the classroom, an expulsion, and for reasons that were incomprehensible to me. This humiliation has accompanied me to the present day.

Vienne Jews are forced to wash pro-Austrian slogans for the cancelled referendum from the sidewalks

(March 1938, photo: Wikimedia/USHMM, Public Domain)

Paul Back reports:

My grandmother’s apartment became a sort of family news center. The family was following the situation and, at first, didn’t panic. They became restless only much later, when the sanctions against the Jews were proclaimed, or when actions began, like street sweeps, harassment and verbal abuse. You began hearing of people being kicked, or attacked, or that someone was taken away. But people were still deluding themselves. People knew it was bad, but didn’t know how bad it would get. One of the few sanctions that got under my skin, because I was directly affected by it, were the signs on park benches that were written with “only for Aryans” or “not for Jews.” I often went for walks with my mother or with my cousins and we used those parks and played there. All of a sudden we weren’t allowed to sit on the benches anymore.

Original recording of Paul Back (Source: Centropa)

Schembera, Verena (2008): Das „Anschlusspogrom“ 1938 in Wien. Diplomarbeit. Universität Wien.

Hofreiter, Gerda (2010): Österreich verlassen? Die Situation der österreichischen Juden nach dem Anschluss (S.19-27), in: Allein in die Fremde. Kindertransporte von Österreich nach Frankreich, Großbritannien und in die USA 1938-1941. Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

April 10, 1938

Referendum

The Anschluss referendum took place on April 10, 1938. The vote was neither free nor confidential, and numerous people who were being persecuted because of their background or political persuasion were not permitted to participate.

Prior to the election, countless propaganda campaigns took place and the state-controlled media advertised for the referendum on an unprecedented scale. The officially announced result implied that 99.7% of votes cast were for the Anschluss. Voters were under enormous pressure to vote for the “desired” result at the polls.

(Photo: Wikimedia, Public Domain)

(Photo: USHMM/National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, ID:306-NT-969)

August 8, 1938

Establishment of the Mauthausen Concentration Camp

As early as two weeks after the Anschluss, the Gauleiter of Upper Austria, August Eigruber, declared the establishment of the Mauthausen camp. On August 8, 1938, the first prisoners were transferred in and directed to build up the camp and quarry operation. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, people from all across Europe were deported to Mauthausen and used for forced labor. They had to work primarily in quarries and for the war industry.

By May 5, 1945, the day the concentration camp was liberated, around 190,000 people were imprisoned in Mauthausen and its satellite camps, at least 90,000 of which were killed.

(Photo: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 192-342 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Fabréguet, Michel (2002): Entwicklung und Veränderung der Funktion des Konzentrationslagers Mauthausen 1938-1945 (S.193-215), in: Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Entwicklung und Struktur. Band I. Hrsg. Ulrich Herbert, Karin Orth und Christoph Dieckmann. Frankfurt am Main: Wallenstein Verlag.

Bundesanstalt KZ-Gedenkstätte Mauthausen: Das Konzentrationslager Mauthausen 1938-1945, unter: https://www.mauthausen-memorial.org/de/Wissen/Das-Konzentrationslager-Mauthausen-1938-1945

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Holocaust Encyclopedia – Mauthausen, unter: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/mauthausen

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Holocaust Encyclopedia – Mauthausen: Forced Labor and Subcamps, unter: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/mauthausen-forced-labor-and-subcamps?series=18606

After the Anschluss:

Jewish Immigration to Palestine

The increasing threat facing the Jewish population from the Nazis put greater pressure on Jews in Austria to emigrate.

For many, the goal was to leave for Palestine. In order to receive permission to leave, a “Hakhshara” (Hebrew: preparation) was often completed to make the departure easier, at the end of which a workers’ certificate was issued. Besides learning Ivrit, acquiring the knowledge necessary to setup a community was prioritized. This mostly included skills in manual labor, home economics, and agriculture. Along with the hope of possibility for emigration, the Hakshara courses also offered young people psychological support, since many were unemployed and being persecuted because of their Jewish roots.

(Photo: Centropa)

Paul Back reports:

We needed a certificate for Palestine […] Getting these papers was very time-consuming and thus the reason why many older or less mobile people were unable to flee. They said to the younger people, “go in the meantime, we’ll come afterwards.” Everything hinged upon this affidavit, death or life! We had a radio, but listening made us more depressed – because of the victory announcements or the grandiose speeches from the Germans.

My mother didn’t see any other option for us but emigration and so attended a retraining course for hairdressing. There were many of these kinds of courses set up especially to train people in careers that would help them find work in a new country. Though she never ended up practicing the trade.

Original recording of Paul Back (Source: Centropa)

Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden: Hachschara, unter:

http://www.dasjuedischehamburg.de/inhalt/hachschara

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung Deutschland: Palästina als Zufluchtsort der europäischen Juden bis 1945, unter: http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/gerettete-geschichten/149158/palaestina-als-zufluchtsort-der-europaeischen-juden

November 7, 1938

Attack on Legation Secretary Ernst Eduard vom Rath

On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan (see picture) shot Legation Secretary Eduard vom Rath in the German Embassy in Paris after learning that his family was part of the mass deportation of Polish Jews from Germany – the so-called “Polenaktion” [Polish Action]. He originally wanted to shoot the ambassador. Herschel Grynszpan did not attempt to flee after the attack and allowed himself to be arrested. Rath died on November 9 as a result of the attack, which the Nazi leadership used as an excuse for the Kristallnacht pogroms.

Although the public only learned about the attack on November 8, the first assaults on Jews and their property had already begun on November 7 in the province of Kurhessen and the Gau Magdeburg-Anhalt.

(Photo: Wikimedia/Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1988-078-08 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Mommsen, Hans (1988): Die Pogromnacht und ihre Folgen. Stuttgart: Verlag Klett-Cotta).

Korb, Alexander (2007): Reaktionen der deutschen Bevölkerung auf die Novemberpogrome. Saarbrücken: Dr. Müller Verlag.

Schumacher, Vivienne (2008): Pogromnacht 1938: Attentat und Propaganda, unter: https://www.ndr.de/kultur/geschichte/chronologie/Pogromnacht-1938-Attentat-und-Propaganda,novemberpogrom102.html

November 9, 1938

Kristallnacht Pogrom

After the attack on November 7, a large-scale propaganda campaign was put into motion condemning the attack as an example of the “conspiracy of international Judaism.” Following Rath’s death on November 9 as a result of the attack, Goebbels called upon top-ranking party and SA functionaries to conduct anti-Jewish campaigns across Germany, for which he received Hitler’s backing.

The Nazi Gauleiter and director of propaganda issued the initial orders to local offices on the evening of November 9, following which terror squads in plainclothes – the SA and SS in particular – barged into synagogues, which they then vandalized and set on fire. During this time, the security police led a wave of arrests to which around 30,000 Jews fell victim. These were mostly male Jews who were then sent primarily to the Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Buchenwald concentration camps. The number of causalities amounted to at least 91. However, historians estimate that the actual number of casualties was much higher.

“In Vienna, 27 Jews were murdered, 88 were seriously injured and mistreated, 6,547 Jews were arrested and over 4,000 business were destroyed. […] A total of 42 Jewish temples and prayer rooms were blown up and set on fire over the course of November 10, 1938.” (City of Vienna)

Mommsen, Hans (1988): Die Pogromnacht und ihre Folgen, in: „Die Architektur der Synagoge“. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta Verlag.

Wien Geschichte Wiki: Novemberpogrom. Abrufbar unter: https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Novemberpogrom [zuletzt abgerufen am: 11.09.2018].

USHMM: “Kristallnacht”, under: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/kristallnacht

USHMM: Bibliographies: Kristallnacht, under: https://www.ushmm.org/collections/bibliography/kristallnacht

Witness Testimonies

Sophie Hirn

Sophie Hirn was nine years old when she experienced the November pogroms. She reports on how being excluded by the Nazis ultimately strengthened her relationship to Jewish tradition.

Edith Brickell

Edith Brickell was fifteen years old in 1938 and later wondered why her parents underestimated the threat posed by the Nazis.

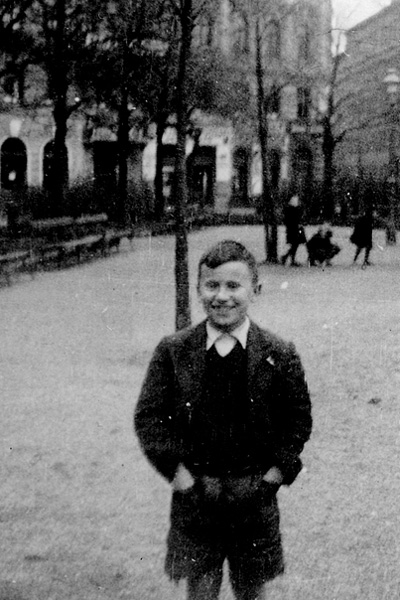

After the Kristallnacht Pogrom

Start of Kindertransports

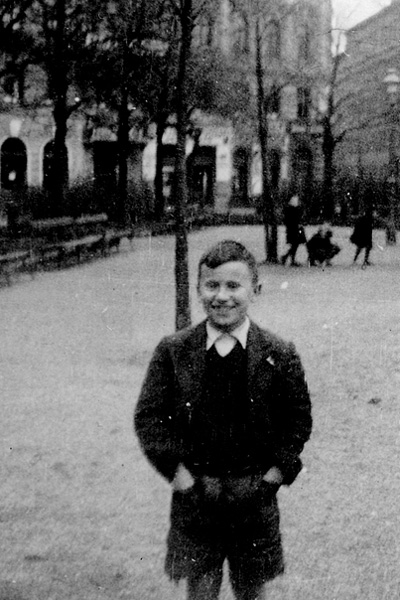

Following the Kristallnacht pogroms and their impact on the Jewish population, the British government decided to accommodate Jewish children in order to protect them from persecution. The first Kindertransport took place on November 30 in which 196 children were brought from Berlin to London. Until September 1939, around 10,000 children from Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Austria were rescued in this manner.

Along with Great Britain, Sweden, the USA, Holland, Belgium, France and Switzerland also participated in the rescue mission. Before the children were given permission to flee, they had to negotiate numerous bureaucratic hurdles. The authority responsible for this in Vienna was the Jewish religious community.

Numerous original documents about the Kindertransports can be accessed in the online archive of the Vienna Jewish Community.

In the online archive of the Jewish Community of Vienna numerous original documents can be accessed about the Kindertransports.

Online Archive of the Jewish Community Vienna: Kindertransporte,

under http://www.archiv-ikg-wien.at/archives/flucht-vertreibung/?tab=2014&topic=2171

Hofreiter, Gerda (2010): Allein in die Fremde. Kindertransporte von Österreich nach Frankreich, Großbritannien und in die USA 1938-1941. Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

Stadt Wien/Geschichte-Wiki: Kindertransporte, unter: https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Kindertransporte

Online-Archiv der Israelitischem Kultusgemeinde Wien: Kindertransporte,unter http://www.archiv-ikg-wien.at/archives/flucht-vertreibung/?tab=2014&topic=2171

Windischbauer, Elfriede: Kindertransporte 1938/39 nach England. Lernmaterial für die Sekundarstufe 1, unter: http://www.erinnern.at/bundeslaender/oesterreich/lernmaterial-unterricht/methodik-didaktik-1/744_Kindertransporte.pdf [PDF]

Jewish children on the first Kinderstrasport reach the English port of Harwich on December 2, 1938.

(Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum / Instytut Pamieci Narodowej)

Kitty Suschny reports:

Ilse and I wanted to go to Palestine at first. We went to the Palestine Office [the Palestine Office managed entry to Palestine] on the corner of Marc Aurel Strasse [1st district] and Vorlaufstrasse and submitted everything.

It cost money, unfortunately, and my mother didn’t have much more. The pension was getting smaller and smaller. My mother complained because it cost so much money.

The people at the Palestine Office said that there was an agricultural school outside of Tel Aviv that we could register for. My friend and I were then walking through the small park along the canal. Mrs. Maurer and Heinzi came our way and said, “get to the Jewish Community right away; there is a Kindertransport to England there.” That was after November 10th, 1938. Mrs. Maurer had already been to my mother and had my papers. My mother didn’t come since she had poor eyesight; she had glaucoma. You couldn’t operate on that back then. Mrs. Maurer went with us to the Jewish community and registered us for the Kindertransport to England. We had to undergo a medical examination. There they tried to separate us out.

Original recording of Kitty Suschny (Source: Centropa)

Resources

Want to learn more about the November Pogroms?

The reports and films featured on this site are just a glimpse into the multi-faceted history of the November Pogroms in 1938. We’ve put together an extensive directory of resources to help you deepen your knowledge.

The image in the background shows a destroyed shoe store in Vienna on November 10, 1938

(Photo: Wiener Library/DöW F. Nr. 6392)